Growth, inequality, and the future of capitalism

Continual growth has been our background belief about how the economy works for 150 years. Perhaps it is time to return to those thinkers who didn't make this assumption.

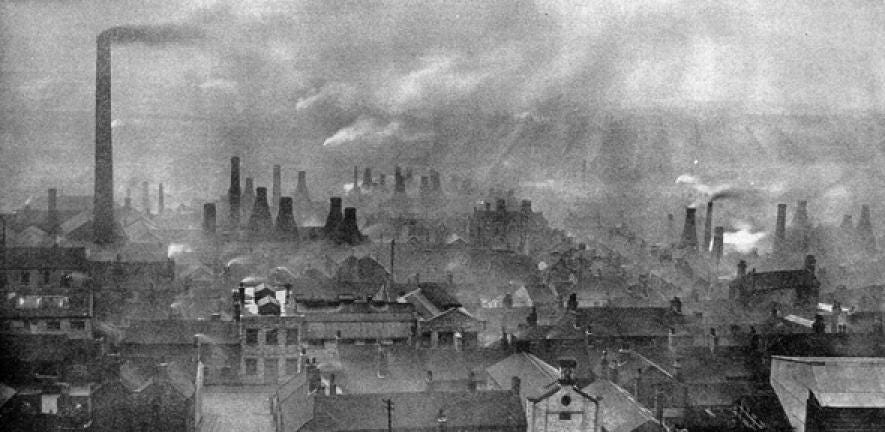

Potteries landscape, 1926. Source: Wellcome Collection. Creative Commons licence.

Been putting together some notes on growth and contemporary capitalism. There’s a definite sense, I think, in which it is now necessary to place growth as such in its context: that this was something we have had for a long period of time, but which is now looking increasingly shaky. Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth does this, but obviously only for the US, and through heavy reliance on what seems to me to be an excessively speculative technological determinism. But I think we need to historicise growth: to think of economic growth not as the permanent background music of life, but as something that for most of human history scarcely existed, has enjoyed a period of two centuries or so in existence, but about which it is an intellectual error to assume will continue.

In particular, the contemporary discussion of inequality tends to think of growth as precisely something external – something beyond the question of the distribution of growth, let alone as something that may itself be contingent in human history. Thomas Piketty’s work formalises this – the famous r>g equation at the centre of his Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which says inequality will increase when the returns to wealth are above the rate of growth. But to historicise growth means not just attempting to account for its progress in the past (plenty have done this, providing GDP estimates for colossally long periods of time). It is also necessary to historicise how we think about growth and inequality, and so be able to step back a little from the background assumptions we tend to make about both.

Growth as an emerging issue

Early theories of material progress, like (most notably) those of A.R.J. Turgot, held that as technology advanced and the division of labour became more complex, society’s material output would grow – but so, too, would inequality, the inevitable result of an increasing stratification of talents and tasks. Later economists, as the discipline began to consolidate, adopted the same mechanism: Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson both had a theory of history in which civilisation itself developed through a series of increasingly complex, materially richer, but more unequal “stages” of human development, associated with a particular technology. At every point, the growth of material output meant also - inevitably - a rise in inequality. Inequality, then, was the mark of progress and civilization as such.

Thomas Robert Malthus, his name today a byword for prophecies of ecological doom and mass poverty, proposed a mechanism like this. Whilst (in his 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population) his model held that the feckless poor would overbreed, and so overconsume, thus being forced back to subsistence levels of income by the hard facts of limited food supplies, civilisation itself would be maintained by an elite class who could continue to enjoy the benefits of a growing output of luxury goods. Material progress would happen in Malthus’ world. It just wouldn’t happen for everyone: society was doomed to become increasingly unequal as a result. The elite had a moral duty (in Malthus’ view) to attempt to alleviate the worst of inevitable poverty, but this would not extend so far as to involve government action in any meaningful way.

The break with this view - of a necessay level of inequality, if growth is to happen - starts to emerge clearly with David Ricardo and his systematisation of a theory of distribution in capitalist society. Like Smith and the other early economists, Ricardo had a theory in which the limits to agricultural productivity condemn the returns to capital to tend, eventually, towards zero. But Ricardo’s application of a labour theory of value turns this into a conclusion about the distribution of capitalism’s output. Increases in wages are possible, but only (in the long run) at the expense of capitalist profits. Workers can become better off in real terms if capitalists are made worse off, in the long run. The other possibility Ricardo offers for a rising money wage is “the increasing difficulty of providing food and necessities.” (The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, ch. XXI). This increase in the money wage would imply labour receiving a growing share of any remaining growth and – as assorted contemporary radicals gleefully noted – limited prospects for the future enrichment of capitalists. Note that this model is not Malthusian: lower growth might end up with less inequality.

It’s worth placing this in economic context. Industrial capitalism, at the time of Ricardo’s writing in 1817, was a fragile creature. The “Industrial Revolution”, as we usually think of it – all those dark satanic mills, chid labourers, soot-blackened walls in Northern towns, etc etc – applied to only a tiny (if expanding, and eventually decisive) part of the British economy. It was only after the mid-nineteenth century that industrialisation looks anything like the dominant or even settled form of organised production. This was a system, in its early years, beset by what seemed to be continual and seemingly near-terminal crises – dynamic, yes, as everyone noted; but also wildly destructive, and perhaps self-destructive. It should not be surprising that contemporary analysis – including that of Karl Marx – tended to think of the problem of capitalism more in terms of the barriers to growth and the problems of instability than to seek out the point at which everything is placidly in equilibrium.

Stabilisation and growth

Its only with the clear stabilisation of the core of the system from the 1850s or so that the issues of its long-term prospects comes to the fore. The “Engels Pause” in real wages ended mid-century, and wage rises became more widespread in the United Kingdom, reaching most obviously first into a “labour aristocracy” of the working class but generalising somewhat into broader layers before the First World War. gs of work and child labour was limited, and significant investments finally made into sanitation and public health. Industrialisation spread and rooted itself in America and Europe, with the United States becoming, by the end of the century, the largest national economy on the planet.

John Stuart Mill was one of the first writers in economics to emphasise this possibility of stability, pre-empting actual stabilisation of the system in his 1848 musings on a “stationary state”:

It must always have been seen, more or less distinctly, by political economists, that the increase of wealth is not boundless: that at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the stationary state, that all progress in wealth is but a postponement of this, and that each step in advance is an approach to it. We have now been led to recognise that this ultimate goal is at all times near enough to be fully in view; that we are always on the verge of it, and that if we have not reached it long ago, it is because the goal itself flies before us. The richest and most prosperous countries would very soon attain the stationary state, if no further improvements were made in the productive arts, and if there were a suspension of the overflow of capital from those countries into the uncultivated or ill-cultivated regions of the earth...

It is scarcely necessary to remark that a stationary condition of capital and population implies no stationary state of human improvement. There would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of mental culture, and moral and social progress; as much room for improving the Art of Living, and much more likelihood of its being improved, when minds ceased to be engrossed by the art of getting on. Even the industrial arts might be as earnestly and as successfully cultivated, with this sole difference, that instead of serving no purpose but the increase of wealth, industrial improvements would produce their legitimate effect, that of abridging labour.

(J.S. Mill, The Principles of Political Economy, 1848)

His moralising take on this (that “there would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of mental culture, and moral and social progress…”) has been taken up and adopted by generations of liberal steady-staters since, including J.M.Keynes’ much-cited comments on how we would all be working three hour days by the 2000s. Mills, it should be noted, remained a Malthusian throughought (“no one has a right to bring creatures into life, to be supported by other people”). Keynes, notoriously, was director of the British Eugenics Society from 1937 to 1944.

But I want here to pick up on the theoretical claim, rather than the moral speculation. What Mill places in the centre of his long run view – rising productivity, what he calls “industrial improvements” – is diverted in his system into the “increase of wealth”, rather than “abridging labour”. Marx also views productivity as central to capitalism’s success, but does not leave us with a developed set of views about the system’s long-term prospects – rather selfishly dying before finishing his life’s work in Capital, and thus leaving future Marxists with many super fun arguments about the status of his falling rate of profit. There is a version, in Marx, of Mill’s choice about future productivity – we could choose to live a life of egalitarian plenty on the back of productivity improvements (“fishing in the morning, hunting in the afternoon, and criticism in the evening” or whatever it was) but whereas in Marx this would require, as a minimum, a political challenge to the authority of capital, in Mill (as in Keynes) it would require capitalists to want to be nicer.

The ambiguity in Marx on the core point of growth, however, comes through in his theory of capital as such. His theory of capital is a conceptual breakthrough on his part – he moves on from the other classical economists in proposing that capital exists not merely as the accumulation of wealth (as Piketty still does), or even the accumulation of prior labour (as both Smith and Ricardo did), but as a separate social institution that organised society’s capacity to produce. This social institution, furthermore, contained within itself the incessant drive to accumulate – it was the defining feature of capital, in Marx’s system, that it strove for its “self-expansion”, that is, any unit of capital was compelled by the wider existence of the social structures that supported it – primarily, in his day, freely competitive markets – to always seek to grow in size. The ambiguity here is what then happens at the level of society as a whole: does the compulsion, the “immanent law” of the self-expansion of all these individual capitals – all those competing firms - then result in economic growth for society as a whole, or does it it hit barriers?

Marx, I’d argue, never proposes an entirely conclusive answer to this. Crucially, if those barriers to growth do not exist, then capitalism can continue to grow indefinitely, under Marx’s system. If capitalism is going to grow indefinitely, there are, in turn, no upper limits on what workers in capitalism can plausibly earn. (Growth may make capitalists a lot rich. But it can at least make workers a little bit better off, too.) And if there are no limits on what workers can earn, and increases in those earnings constitute a market for the output of capitalism (a point Marx makes directly in the Grundrisse, and vol.2 of Capital), then not only is there no upper limit on working class earnings, but paying workers more might actually be good for capitalism. Growth need not produce inequality.

This is the key point. If growth under capitalism need not produce inequality then it need not be a direct concern for socialists: there can be a simple pass-through from the introduction of productivity-improving technology to workers’ wages and, potentially, even falling inequality.

Stages of history

It is this prospect – of equality-increasing growth – that came to form the core of socialist thought as it developed post-Marx. It could be slotted into Marx’s broader historical scheme, with technological advances driving (potentially) equality-producing growth. On a grand scale, one version of Marxism offered this rather deterministic prospect. Texts like The German Ideology certainly leaned in the direction of technological determinism, and later socialist thinkers introduced a decidedly deterministic, “stages” theory of histoical development. Engels’ Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State pushed this back also into a stages theory of pre-history, with early humans moving from “primitive communism”, through “savagery” and then “barbarism” to “civilisation” as agricultural technology developed. (The terms are borrowed from pioneering anthropologist Lewis Morgan.) But in the last stage of human history, where the technology would allow a leap into the “realm of freedom”, this sequence was finally reversed: technology would become so advanced that inequality was no longer necessary.

Contemporary writing on “fully automated luxury communism” is the most obvious adaptation of this theme, but a version of growth-producing-equality is fundamental to how the social democratic left thinks about society. As capitalism in the Western world stabilised, following the horrific decades of the first half of the twentieth century, growth that reduced inequality came to appear as a real possibility. Capitalism, it was believed, had been tamed thanks to “Keynesian” economic management; remaining inequalities produced by the growth engine could be resolved through redistributive taxation, and judicious government spending; and the institutions capitalism had developed, like trade unions, could themselves contribute to economic growth by bargaining with capitalists over the division of its spoils between profits, wages, and investment in “productivity coalitions”. The classic political statement of the growth-reformist case remains Anthony Crosland’s 1956 The Future of Socialism, which urged the abandonment of the left’s concerns with the organisation of production and instead pressed a focus on the more equal distribution of capitalism’s spoils.

More formally, the model of economic growth introduced by Robert Solow and Trevor Swann - also in 1956, and still the backbone of conventional growth models today – showed that a ”steady state” rate of continual growth could be found under capitalism in which everybody – workers and capitalists – received their fair share and in which only the rate of technological progress determined the overall rate of growth. By happy and spectacular coincidence/careful construction, this balanced growth path could be found at the precise same point at which prices in free markets for both capital and labour would gravitate towards, if left to their own devices. Extending Solow’s original model to try and also model technological progress (“endogenous growth”) leads to some pretty wild conclusions, taken up with merry abandon in Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism, on the acceleration of growth into the future (growth means more technology means more growth and so on).

More realistically, putting all this together creates a continuum of options for growth-producing capitalism: of a low-growth, high inequality setting (the “Third World” for much of the post-war period); of a high-growth, high inequality setting (China for the last forty years); and various points inbetween, with some growth often being traded for some reduction in inequality.

So the CPC, broadly speaking, is attempting (or says it is attempting) to navigate the Chinese economy to some point in the moderate growth/moderate inequality section of the continuum from its massive growth, massive inequality Dengist former setting. Much of contemporary social democracy argues that it wants to find some point around the somewhat higher growth, somewhat lower inequality section. Clearly, if growth is being produced at all, some part of this continuum involves win-wins - higher growth, lower inequality relative to whatever position an economy is currently set at.

If growth is being produced. But this raises the question posed by Mill: can growth continue indefinitely for the whole economy? Mill thought not, and that this could then lead us into a steady-state liberal utopia of wholesome intellectual pursuits and working class abstinence. But a theory of capital as something other than the passive accumulation of labour, or the legal veil under which technology is employed, leads us back into a world described by Ricardo: in the steady-state of zero growth, workers only become rich at the expense of capitalists. And if - just for the sake of argument - we live in a world in which hard barriers to prosperity emerge from environmental causes, we have to also conclude that rising costs of living will turn into hard struggles over the distribution of resources. If Marx offered an general theory of capitalist growth, it is Ricardo who re-appears as its theorist of decline.

Speaking of Deng Xiaoping, I’ve been listening to the first couple of episodes of this short podcast series, organised around his 1992 “Southern Tour” - in which Deng attempted (successfully) to frighten the more conservative elements of the CPC leadership into pursuing his market reforms with more viguour. Thirty years later, Xi Jinping’s speech possibly terminating that process is worth a read - not least because just how very “New Labour” it is in its stress on social mobility, the desirability of hard work, and its reassurances that the mega-rich need have little to fear. (The anti-productivity “lying flat” movement is singled out for direct attack.)

Meanwhile, Will Davies deals summarily here with Britain’s very own Pooh Bear leader (blonde, lazy, continually rescued from scrapes by his friends, etc): “Being recognisable and entertaining, Johnson provides a focal point; and because everyone knows this, it is then possible to rally people around him, rather as people might meet near a famous landmark.”

Trade unionists and socialists in Salford, Greater Manchester are organising to transform the provision of social care in the borough - Basit Mahmood covers it for Tribune.

Not quite comprehending this James, if under a socialist programme we switched to putting our efforts into (say) building more useful things such as schools, colleges and hospitals instead of putting the valuable earth resources into useless personalised trinkets of the capitalist consumer market; then we would still be increasing GDP as we are still actually building the physical “stuff” and increasing services for peoples’ use. A net social gain.

Now the only way that you could actually shrink GDP without society being in a more impoverished state is if the shrinkage exactly matched efficiency gains in the same period of time. Otherwise all shrinkage in GDP would result in some sort of impoverishment overall. Quite how that impoverishment was distributed would be another matter of course.

So in order to protect the environment what we are after surely is Green Growth not No Growth?