Can the left survive covid?

There are no historic guarantees it will. Right now, the British left is consigning itself to irrelevance.

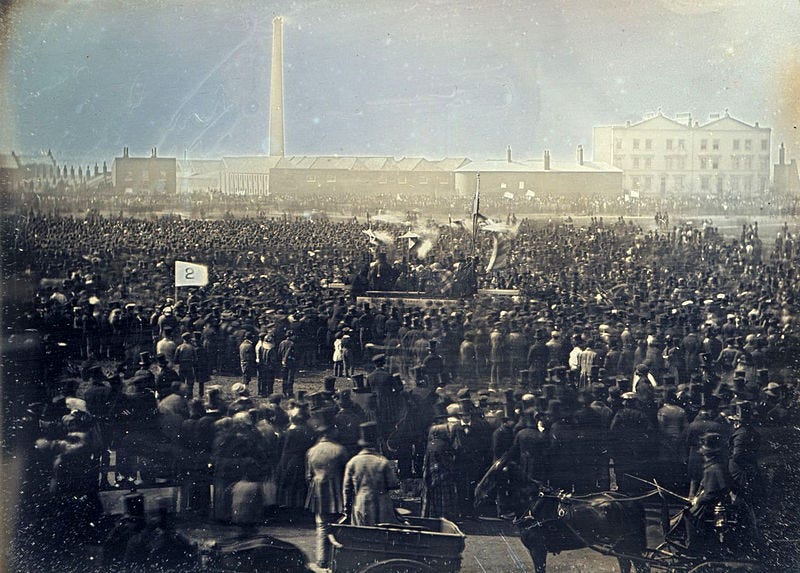

Chartist demonstration, Kennington Common, 10 April 1848. Source: William Edward Kilburn, via Wikimedia Commons

We should be very clear about what happened in the last week. The British left, with some rare exceptions, collectively flunked the central challenge of covid politics. Failing, in its great majority, to oppose both mandatory vaccinations for NHS workers and vaccine passports was not only an offence against good public health management in favour of knee-jerk authoritarianism. Offering political support for the Johnson government was a significant political error that yet again revealed the extent to which covid-19 has found the British left intellectually, organisationally, and politically lacking. And since the politics of covid now constitutes politics as such, failure here is of a profound character, raising the question in the title. Can the left survive covid?

Sitting this one out

For socialists and social democrats to effectively sit the debate on restrictions out, allowing both sides of an argument to be dominated by versions of the right – the reactionary government voicing the statal logic of passports, the reactionary protestors acting as its plebeian opposition – was and is a mistake. The latter are gaining in strength and, since both passporting and mandatory vaccination will be ineffective in restraining the Omicron variant, have been gifted a powerful political argument against future restrictions. The space in which covid politics operates is not some temporary aberration: it is where politics now actually happens. (This ought to be obvious, after nearly two years.) The British Querdenken are moving rapidly to occupy that space. And yet the radical left appears to be acting as if, at some point in the near future, the terrain we operate on will return to its familiar, pre-pandemic shape and we can get back to railing against “Tory austerity” or “neoliberalism” or whatever familiar monster we prefer to fight.

Labour’s prior opposition to vaccine passporting, stated with some clarity over the summer, into support “in the national interest”, has a similar flawed logic. From a tactical point of view, Labour’s flop into unconditional support for the Tory government reduces its room for later manoeuvre on the question. With covid cases rising rapidly, the government is likely to request more restrictions – they are being openly discussed - and, were Labour to object or raise conditions on support such as improved sick pay, ministers can turn around and make the (not unreasonable) argument that if Labour didn’t object when things were less bad – why is the party making trouble now?

This lurch back into lockstep support for a plainly incompetent government is occurring just as the first signs emerge that the public’s tolerance for restrictions has reached breaking point. There are many reasons for this: a significant contributory factor has to be the overselling of vaccines as the highway out of covid. At least anecdotally, it was widely believed we would jab once or twice and be done. We bought a rapid take-up last year at the expense of a longer-term erosion in public confidence. The costs of a return to restrictions, or of simply accepting the necessity of further restrictions, will themselves be heavy and unequally borne.

This, in turn, reveals the more serious, strategic bind that not only the Labour leadership but the broader left beyond have tied themselves into. It should have been obvious since around March 2020, when the World Health Organisation declared covid-19 a pandemic, that the period of time over which the virus would be an acute social problem was likely to be measured in years rather than months – let alone the weeks Boris Johnson originally forecast. Even with the impressively speedy arrival of the vaccine – itself predictably the source of further disruption and injustice – this extended period was always likely to be the case.

But this plausible timing has simply not factored as a calculation across the spectrum: not for the UK government, who have now (quite astoundingly) failed to prepare adequately for winter covid waves during two summer lulls. Not for the broad spectrum of the left, where the utopia of “Zero Covid” has provided one version of short-term thinking, uncritical support for government “in the national interest” a second variant, and a smug and unpleasant turn on the unvaccinated a third. In all three cases, the unstated assumption is that normal life (and normal politics) is temporarily suspended by covid but will resume again soon. All three – radical, centrist, and liberal – are wrong.

Both the centrists and the liberals are happier to operate to a political logic of subordination to the core interests of the state and major capital, aiming to smooth the rough edges rather than present an alternative version of them. The British political system offers a space for a second party that expresses a version of those core interests, and whilst this generally means the second party’s exclusion from actual power, with the Tories dominating governments of the last hundred years, it is at least reasonable to think that the secondary space can be occupied and a chance at government created for the centre-left. New Labour’s striking success demonstrated the plausibility of the strategy before the 2008 financial crisis.

The difficulty, after 2008, is that actually defining those interests for state and capital, and winning wider social support for them, has become harder in a world-system no longer operating to neoliberal rules, and where popular rejection of those same rules is now widespread.

Jeremy Corbyn’s time as leader of the second party of British capitalism offered a redefinition of those state and capital interests, post-2008. Corbyn presented a possible government that would forge a more state-centred and more egalitarian social settlement, remaining well inside the boundaries of capitalism but offering a different vision of it. But the Corbynite political project proved unsustainable – although chunks of the Corbyn economic programme, suitably defanged, have made their way into Conservative government policy via a process of learning and adaptation that the Tories are infamously good at.

Covid has further worsened the problem of defining those interests, at the same time as it has made the necessity of doing so far sharper – since to fail to define a policy and programme now is to risk society and economy later becoming overwhelmed by a pandemic disease. The disputes in government over applying fewer or greater restrictions are, for example, the result of this problem, and the characteristic lurching of the Johnson government, from easing to lockdown and back again, is the product of its failure to decisively resolve it. But governments everywhere, outside of authoritarian regimes, have suffered from similar uncertainties. Johnson’s personal inadequacies don’t help, but the pattern is common and will most likely continue when he is gone.

The political problem for the centre-left and the liberals, however, is that the logic of subordination to those core interests, whilst pushing for some amelioration of them – some more redistribution, some wider definition of social rights, say – becomes much harder if those core interests are not clear. They had become shaky over the decade after the crash, as the Brexit referendum and then the 2017 General Election result showed: popular legitimacy had drained away from the Cameron-era austerity-and-neoliberalism option, whilst powerful actors – notably China and Big Tech – were prepared to break with neoliberal norms. Johnson’s initial plans for government – get Brexit done, end austerity, address regional imbalances – attempted a redefinition. The pandemic threw these calculations out of the window. The direction for private capital looks fairly clear – a greater dependency on the state, and a greater use of data, continuing pre-covid trends – but the direction of states and governments over the newly-critical questions of public health is now subject to serious short-run uncertainty.

There is, in these circumstances, no obvious, immediate interest for the centrists and liberals to offer their subordinate support to; instead, as we have seen since spring 2020, they end up simply tracking the twists and turns of short-term attempts to manage the pandemic. If the pandemic continues – and we have to assume it will – the lurching will continue. And it seems reasonable to assume that, over the longer term, tracking the lurches will do Labour few favours.

Subordination

The same logic of acceptable subordination does not apply to the radical left. Of course, it is always necessary to operate in some form of coalition with the centrists and the liberals if the radical left is serious about the need to form a government, and the Labour Party provides the space where that can happen. But if the radical left is critical of capitalism, as a minimum its programme has to include a redefinition of the interests of the state and capital to the benefit of wider society – whether expressed in these rather abstract terms or not.

What we have singularly failed to achieve so far is to describe that redefinition in conditions where covid is a long-term fact of life. “Zero Covid” is a demand to pretend otherwise, regardless of economic and social cost; it is the state-centred inverse of the market-centred Qeuerdenken commitment to the same illusion. Both depend on the bad, utopian idea that covid can be simply removed from our lives. But by this point we can no more banish covid than we can now halt climate change: the question for both by now is fair and effective restraint and management, not abolition. The point isn’t to do nothing about either. It’s to do what will work.

The result of this utopianism is a radical left increasingly devoid of purpose. Its state-centred instincts mean it can, perhaps, speak to that slender section of the population that remains somewhat enthusiastic about further restrictions. (It is interesting to note that Labour’s 2019 voters are the most supportive of lockdown.) It can neither challenge government effectively, nor challenge the conspiracy theorists and the libertarian right with any credibility. If the radical left is serious about forming and leading a government in the future, this is, of course, the worst possible place to be in. More than bureaucratic ruses by Labour full-timers and political attacks in the press, it is this more fundamental lack of direction and purpose that is slowly killing the left as a meaningful political force.

Left-wing hobbyism

Of course, becoming pointless doesn’t have to mean the literal end of the left. Those who remember neoliberalism will know that it is always possible, in a somewhat democratic society, to live a contented life with leftwing “activism” as an enjoyable alternative hobby for people who might otherwise be attracted to brass rubbing or fly fishing, complete with its own arcane historical disputes, specialist shops, and opportunities (for those so inclined) for minor celebrity. Twitter in recent years has added the additional thrill of immediacy: you, too, can tweet Kieth-as-ham memes at Keir Starmer, if you like. It makes no difference but it passes the time.

The moments in those three decades or so where the sealed tomb of left-wing hobbyism has been cracked open is when the left has managed to intervene decisively in a core political question. The Iraq War movement, without which little of British politics for nearly two decades makes much sense – including, perhaps most notably, persistent public hostility to military intervention – provided one such instance. The election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, on the central political issue of opposition to austerity, was another. In both cases, of course, prior organisation provided the capacity for the intervention, with the formation of a national anti-war campaign in the wake of the “War on Terror”, and the creation of a national anti-austerity campaign in the wake of the 2010 election.

The triple losses suffered by the left in and around Labour from December 2019 to February 2020 – General Election, leadership election, NEC election – of course severely disrupted its capacity to organise. So, too, did covid itself: the disease is and will continue to be sui generis in its impacts, and this has weighed against political clarity on all sides. The world is more confusing than it was, and, in an immediate, practical sense, lockdowns are a barrier to conventional political organisation. But we’ve had almost two years of this, now; there’s no further excuse for the spring/summer 2020 magical thinking of a short pandemic.

At the very least, the left needs to begin moving from an emergency response setting to offering immediate, practical steps that resolve pressing questions and that then fit into a broader plan for government. It needs, in other words, to start offering an independent programme: “Zero Covid” isn’t this – at best, it’s is the hoped-for outcome of a programme – and nor is trailing obediently behind a government that is manifestly failing. It’s grim, but the anti-vax/anti-lockdown right does have a rudimentary programme, boiling down to the call to keep things open and see what happens.

Alternatives

There should be no serious question that lockdowns and restrictions on social life are a last resort for the worst situations. In the case of calls for a “circuit breaker”, it is surely now necessary to place the additional demand that this is limited in duration – not to some arbitrary date, but to some medical fact: a target for stabilisation in case numbers, say. Demands for increased Statutory Sick Pay and inflation-breaking pay rises across the public sector are important, although situated on somewhat more familiar terrain.

But we have to think a few steps ahead of this. Broadly, the government has faced choices about costs and control in managing the pandemic. To avoid costs today – for instance in providing adequate staff pay or SSP – it will risk control in the future, imposing lockdowns when forced to do so. Reuben Bard-Rosenberg raised this prospect last year:

Governments may find it politically more desirable to plan for potential surges in demand by have some "firebreak lockdowns" up their sleeve, rather than invest in excess capacity and pay workers enough to maintain that capacity. Thus the NHS will be "protected" through greater powers of social control rather than decent pay.

Every lockdown is a failure of prior policy and we should be clearer about saying this. But beyond the provision of sufficient capacity in our health services, we need to also think more seriously about how society can be organised in ways independent of state control and market forces to cope with long-term covid. I tried to outline a domestic programme at the end of last year:

If our shopping is switching online, can we redesign our high streets to create new public spaces? Additional space is all the more necessary if social distancing has to be maintained. If working from home becomes the norm for millions, can we repurpose underused office space? The thinktank Autonomy has published innovative proposals for workplaces in such a world, reformatting standard office design and building in safer social contact. If not all work can be conducted from home, can we at least reduce the hours we have to spend at work? The use of furlough and part-time working schemes, unthinkable until this year, could move us towards that. If instability is endemic, can we make the case for a universal basic income to provide meaningful security? If we are entering a “90% economy”, with future growth permanently constrained, can we learn to use measures other than GDP growth for economic success – just as Jacinda Ardern’s government has moved towards in New Zealand?

But we face more immediate questions, as shown in the last week. I don’t think we need to make vaccine passporting the decisive strategic question for the left, and drive out all those who fail it. Apart from anything else, since we can reasonably expect to be dealing with covid over the next decade or so, the issues raised by the specific biosecurity intrusion of passporting are going to come back again and again, in different forms. Passes aren’t the same kind of argument as, for example, the Iraq War, whose small band of “left” supporters were quite rightly and reasonably treated by the overwhelming majority, back in 2002-3, as irreconcilable political opponents. For vaccine passports, patiently explaining the issues and moving on to common ground for agreement is a better approach: although with a vote due in Parliament on continuing the measures at the end of January, these specific arguments will return with some force in about a month.

There will be chances, in the next few months, for the left in Britain to change direction. It has to; bar a near-miraculous disappearance of the pandemic, it has no worthwhile future otherwise.

Antifada have a must-listen interview with activists from the Chuang collective in China – scathing about some Western would-be anti-imperialists, detailed on how the popular movements relate to the state in the course of the pandemic. Meanwhile, Phoebe and Hussain over at Ten Thousand Posts interview tech journalist James Vincent: “Robots Should Not Have British Accents”. Also recommended.

Richard Seymour here comes out against the “biosecurity” state being assembled in front of us. I’m less convinced that Benjamin Bratton on “positive biopolitics” offers much of a longer-range guide on how to respond to this, but I’m very glad to see the debate at least opening up. Over the Atlantic, Kim Moody has a detailed analysis of the US strike wave in Spectre.

I’m going to be taking a break from this newsletter for a couple of weeks over Christmas – back in the New Year. Thank you for reading this far, and for the various questions and comments that have come in. I hope you all have a safe and suitably restful holiday.

Great stuff James.

Awesome, we are also suffering a similar state of paralysis of the left in Turkey in the midst of an abundance of possibilities and opportunities because of a deep calcification of the ways of acquiring the reality